In 1921, the renowned Austrian aeroplane and automobile designer Edmund Rumpler presented a completely new, revolutionary vehicle concept at the automobile exhibition in Berlin. In addition to an almost futuristic external appearance with a streamlined teardrop-shaped body and centrally positioned driver's seat, Rumpler's 'Tropfenwagen', or 'Teardrop car', was particularly astonishing due to the engine installed in front of the rear swing axle. Benz development manager Hans Nibel, who was interested in this highly innovative concept, and his chassis designer Max Wagner arranged for a preliminary contract to be signed with Rumpler, who subsequently had an open version of the Teardrop model, together with the associated set of drawings, sent to Mannheim for closer inspection.

Nibel and his colleagues took a close look at Rumpler's design and discovered a need for optimisation. Even back then, motorsport was seen as the ideal basis for recognising the potential of the concept and gaining experience with it. So it was only natural that the first thing to do in Mannheim was to design racing cars that incorporated Rumpler's idea of a mid-engine layout. A total of four vehicles are said to have been built, which bore the name Benz Tropfen-Rennwagen, or Benz Teardrop racing car.

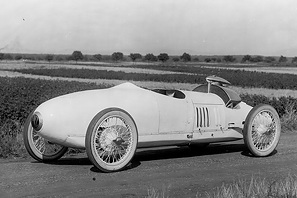

A characteristic feature of the racing cars was that, in addition to the new positioning of the drive unit and transmission, the Benz designers implemented a consistently streamlined body design and made use as much as possible of lightweight construction techniques. In contrast, the basic design of the frame was kept conventional: a pressed steel frame with a U-shaped profile ensured stability. The front wheels were suspended from a rigid axle with a special semi-elliptic spring, which was initially designed as a stub axle and later became a straight axle, while the rear axle was designed as a swing axle - as Rumpler had also already planned. Here, the semi-elliptic springs used, similar in their arrangement to a semi-trailing arm, also took on axle guidance functions. On the front axle, additional friction shock absorbers kept the rigid axle in check. Longitudinal frame members, crossmembers and the front axle, which was also made of sectional steel, had holes of various diameters drilled through them as a means of reducing weight.

The extremely slim and smooth body with its rounded cross-section accommodated two occupants - the driver in the front and the front passenger behind, slightly offset to the left in the direction of travel. Both only peeked their heads out of the narrow body, whose shape was indeed reminiscent of a drop in rapid fall.

After trials with a four-cylinder engine that can no longer be clearly identified today, which was apparently installed in the first prototype of the racing car, a long-stroke 2-litre inline six-cylinder engine with ultra-modern design features followed as the regular engine. The individually positioned steel cylinders, enclosed by a welded-on cooling water jacket, were based on a tried and tested convention from aircraft engines and each featured four overhead valves positioned at a 45° angle to each other in a V-shape. By means of forked rocker arms, these were actuated by two overhead camshafts that were driven by a spur gear set positioned at the rear end of the engine. The use of a Hirth crankshaft with seven roller bearings and bolted together from individual segments was also a very modern solution.

The mixture was formed by two 42 mm Zenith horizontal carburettors. An unmistakable feature of the 'Teardrop' racing car was the radiator, including expansion reservoir, arranged transversely behind the engine and protruding in an arc above the body contour at its upper end. The reservoir was positioned longitudinally above the water box and its design echoed the streamlined basic shape of the bodywork. Power was transmitted by a 3-speed transmission located behind the engine. As the six-cylinder engine had to make do without the increasingly widespread compressor technology of the time, its qualities as a racing engine were only utilised to a limited extent. With a peak output of 90 hp/66 kW at 5000 rpm and a continuous output of 80 hp/59 kW at 4500 rpm, the naturally aspirated engine performed well, but was at a power disadvantage of 30% or more against supercharged 2-litre racing engines.

The 'Teardrop' racing car was braked by means of a mechanically operated four-wheel brake system. Inside shoe brakes were used all round, which were initially located on the inside of the differential on the rear axle and were moved to the outside of the wheels in 1924.

The first use of the futuristic 'Teardrop' racing car took place at the highest level: three cars competed in the Italian Grand Prix in Monza on 9 September 1923, which also bore the honorary title of European Grand Prix. Given its performance deficit compared to its international rivals, the result achieved by the mid-engined car was absolutely respectable, with Italian Fernando Minoia finishing fourth and Franz Hörner fifth, which said a lot about the future viability of the technical concept.

Nevertheless, the inferior performance of the 2-litre six-cylinder engine was more than evident in the race results: while there was only a gap of around 5 minutes between the winner and the third-placed driver after 80 laps and a total driving time of around 5½ hours, fourth-placed Minoia finished a full four laps behind to take the last position among the points. The Solitude Race on the outskirts of Stuttgart, held on 18 May 1924, presented a similar picture. Behind the victorious Mercedes drivers Otto Merz and Otto Salzer, both in a 2-litre compressor racing car, Franz Hörner took third place in the teardrop-shaped Benz. This was also a good result in itself, but on closer inspection it raised the same questions as the race in Monza. Merz and Salzer achieved average speeds of over 103 and 102 km/h respectively, while Hörner never managed more than 90.3 km/h. The conclusion was clear: the mid-engined car with its underpowered naturally aspirated engine was not a candidate for victory in top-class sport, and the good results were mainly due to the innovative overall concept of the teardrop-shaped racing car.

This realisation led to two consequences. On the one hand, the car was hardly ever used in truly prestigious events from that point on, but mainly in various individual national competitions, often in hill climbs. And more and more often with privateer drivers behind the wheel. Secondly, Benz & Cie. developed a sports car version of the teardrop-shaped car with identical technical specifications and additional wings, lighting and small sports windscreens. This opened up a multitude of new starting opportunities in the respective sports car classes of larger races and at events that were exclusively reserved for sports cars. Until the early months of 1926, Willy Walb, Adolf Rosenberger and Carl Hermann Tigler in particular enjoyed numerous successes. Among the highlights were Walb's victories in the summer of 1924 in the racing car class in the Königstuhl hill climb in Heidelberg and in the hill climb and flat race in the Taunus, and in the summer of 1925 in the Badenia Preisfahrt, in the sports car class in the Freiburg hill climb and flat race and in the Hohentwiel hill climb. Rosenberger won the prestigious Herkules hill climb in Kassel with the racing car version at the end of May 1925, setting the best time of the day and a new track record. A modified version of the Teardrop car was used, which was no longer quite as teardrop-shaped as the original version thanks to a radiator housed in the front.

The installation of Ferdinand Porsche as chief engineer of the newly founded Daimler-Benz AG in 1926 signalled the imminent end of the teardrop-shaped car, which had been as ambitious as it was promising, but had not been consistently thought through to the end. Porsche had previously worked as Technical Director of Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft (DMG), so his interests were primarily focussed on his own racing car developments. Nevertheless, Porsche was evidently influenced by the basic concept of the teardrop-shaped racing car, because after leaving the DMG and establishing his own design office, it was reflected in the P-Wagen racing car project he initiated himself in 1932/33. After being taken over by Auto Union in 1934, this gave rise to the mid-engined racing cars of types A to D equipped with V16 and V12 engines.