Ferdinand Porsche, who had moved from Austro Daimler to Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft (DMG) in the spring of 1923 as Technical Director and member of the Board of Management, left his mark not only on production car design but also on racing car design in Untertürkheim from the very beginning. Immediately after the extensive redesign of the 2-litre four-cylinder racing car with which Christian Werner had gone on to win the race in Sicily at the end of April 1924, Porsche turned to a challenging new project.

In order to advance into new performance dimensions within the constraints of the new engine regulations for motor racing that had been in force since 1922, which stipulated a displacement limit of 2 litres, it was necessary on the one hand to make even more efficient use of the compressor, which had already been successfully introduced, and on the other hand to achieve a higher engine speed level. This was the only way in which a sustainable increase in performance could be achieved. Porsche therefore decided to design an eight-cylinder inline engine - the first such engine in DMG's automobile production.

The basic design of the new racing unit was based on the four-cylinder engine with two overhead camshafts that had been successfully introduced the previous year. The individual steel cylinders with the welded-on steel cooling jackets were again designed as blind cylinders, i.e. welded to the cylinder head to form a single unit. The proven concept of gas exchange by means of two intake and two exhaust valves per cylinder was also retained. The latter were again hollow and filled with mercury to reliably absorb temperature peaks. The cylinder heads were fitted with a light-alloy housing that accommodated the valve train. This contained the two camshafts, which actuated the valves via forked rocker arms. The camshaft drive was new: instead of the elaborate vertical shaft solution, Porsche favoured a drive system with a spur gear cascade located at the rear end of the crankshaft.

Porsche also favoured a simpler concept for the crankshaft itself. Instead of the built-up Hirth crankshaft, a conventional one-piece crankshaft was now installed, which rested on five roller bearings.

He also made a fundamental modification with regard to the efficiency of the compressor: while it had previously been at the driver's discretion to switch on the compressor by depressing the accelerator pedal, with the new eight-cylinder engine it ran constantly. At the same time, the previously hermetically sealed updraught carburettor was replaced by a normal suction carburettor.

The results of Porsche's development work were impressive: the output of the eight-cylinder inline engine was now 170 hp/125 kW compared to the 150 hp/110 kW that the four-cylinder engine had achieved in its last development stage. However, the increase in rotational speed was even more impressive. While the predecessor engine had had to make do with a rated speed of 4800 rpm, the similarly long-stroke eight-cylinder engine delivered its maximum power at 7000 rpm - an enormously high speed level given the technologies available at the time.

In order, on the one hand, to be able to transfer the high power satisfactorily to the road and, on the other, to achieve agile handling, Porsche pursued the goal of creating a chassis in which all stable and unstable masses were positioned as centrally as possible and as low as possible between the axles. To this end, he positioned the engine behind the front axle and the two seats just in front of the rear axle. In order to reduce the influence of emptying fuel and oil tanks on handling over the course of the race as much as possible, he positioned the 25-litre oil tank on the left-hand side of the engine. Porsche devised a very special solution for the fuel tank, which held more than 90 litres of petrol: he relocated it to between the longitudinal rails of the chassis frame, where - rounded off at the bottom - it filled the space between the rear end of the transmission and the rear axle.

The chassis remained conventional as far as its other design features were concerned. It consisted of two pressed steel side members with a U-profile, braced together in several places, to which a rigid axle suspended on semi-elliptic springs and equipped with friction shock absorbers was attached at the front and rear. Deceleration was provided by inside shoe brakes on the front and rear wheels.

The theory behind the ultra-modern vehicle concept was one thing - but the real-life use of the eight-cylinder racing car turned out to be far less promising. Both the performance characteristics of the new engine and the handling of the car proved to be problematic. Despite its long-stroke design, the engine suffered from an unfavourable torque curve. It lacked pulling power over large parts of the rev spectrum; the output needed was only realised shortly before the rated speed was reached - but all the more explosively for that. The transmission, which only had three gears, was of little help here, as its inevitably wide gear spread emphasised the lack of elasticity of the eight-cylinder even more.

The unpleasant power delivery of the racing engine met with handling characteristics that were anything but easy to control in racing mode. Although these remained neutral for a long time thanks to the balanced axle load distribution, they became treacherous when the extremely narrow limit range was exceeded. Since neither engines with "peaky" performance characteristics nor unpredictable handling characteristics were part of the usual experience of even high-ranking works drivers in the mid-1920s, it became a real challenge even for the most intrepid among them to exploit the inherently superior performance potential of the eight-cylinder engine in racing.

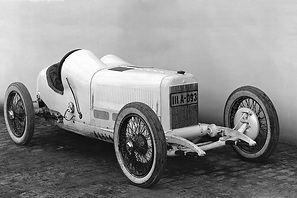

The first version of the 2-litre eight-cylinder racing car, completed in September 1924, featured a flat radiator with a single Mercedes star placed centrally on the radiator tank. The four cars entered a month later in the Italian Grand Prix in Monza, on the other hand, were equipped with a slightly pointed radiator and two Mercedes stars.

The outing in autumn 1924 was not under a good star. Christian Werner, Alfred Neubauer, Louis Zborowski and Conte Giulio Masetti each competed with the new eight-cylinder in the Italian Grand Prix, which was initially scheduled to take place at the beginning of September and was then postponed to 19 October. After Masetti had already retired on the 43rd of 70 laps due to a lack of petrol, Zborowski's fatal accident overshadowed the race and led to the withdrawal of the two remaining cars of Werner and Neubauer.

However, 1925 brought the first successes with the eight-cylinder in national racing events. Werner's victories with the best time of the day in the first ADAC kilometre and hill climb record on the Schauinsland just outside Freiburg in August 1925 stood out. Werner won the race on the Schauinsland in a modified version of the racing car, which was developed on his initiative and adapted to the special operating conditions of hill climbs.

In the following year, 1926, Adolf Rosenberger and Otto Merz, who competed on various occasions with the 2-litre eight-cylinder racing car, also achieved notable successes. Rosenberger with a class victory in the Herkules Hill Climb and a third place in the racing car class up to 2 litres in the Klausen Pass Race, while Merz also scored a class victory in the "Rund um die Solitude" Race in mid-September.

However, the most significant victory in one of the eight-cylinder cars was achieved by Rudolf Caracciola with the four-seater sports car version in the German Grand Prix, which was held on 11 July 1926 on the AVUS circuit in Berlin. It was the first international race in Germany since the end of the First World War.

There were also a number of successes in 1927 in the 2-litre eight-cylinder with its tricky handling. Werner won the flat race over one kilometre with a flying start at the International Freiburg Record Days with his hill climb car with the best time of the day and a speed of 184.1 km/h; he also achieved a class victory in the Hill Climb Record Race on the Schauinsland. On the Klausen Pass, he also won both the national and international races in the racing car class up to 2 litres capacity – now back in the regular version. In Great Britain, Raymond Mays also achieved numerous successes in one of the eight-cylinder models that year – especially in sprint races, where the main focus was on high engine output and the best possible traction.